By Justin Brightharp | YPFP Rising Expert for Energy | July 30, 2023 | Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

This article is the second in a series highlighting different stakeholders’ roles in combatting the effects of climate change. From private citizens and local governments to nations and international bodies, each stakeholder’s role carries explicit and implicit responsibilities. Different stakeholders’ roles are not mutually exclusive, but this series emphasizes where each is most likely to thrive.

While the first piece in this series focused on local stakeholders, this one examines the roles of international bodies and national governments. Historically, the international community—comprised of groupings from different nations—has played a leading role in combatting climate change. Meetings and conferences at the international level hosting representatives from participating national governments produced reports, treaties, frameworks, and goals addressing issues pertaining to effects on the natural environment and human health, among others. The United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in 1972 is considered the first global conference on the environment and has been followed by the Montreal Protocol in 1987, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992, the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2015, better known as the Paris Climate Agreement. These conferences have resulted in declarations and guiding principles, strategic plans, and agreements detailing commitments and goals to be taken by signatory countries.

International Bodies

International bodies have played a significant role in facilitating, financing, and researching global efforts to address the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation.

Facilitation and creating spaces for dialogue around climate change’s impacts is crucial to mitigation and adaptation. Although the impacts of climate change vary widely across localities, it is a global phenomenon that transcends borders, strains resources, and exacerbates conflict between bordering countries. International bodies provide a neutral space for robust conversation, conflict resolution, cultural exchange, and ideation of replicable solutions to combatting the impacts of climate change.

The United Nations has served in this role by hosting several meetings and conferences on climate and the environment. However, there are other international bodies that can and do play a role from a regional perspective. Examples include the African Union, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the European Union, the League of Arab States, and the Pacific Islands Forum. These organizations can address climate specific actions affecting global regions and many of them already have committees and staff dedicated to mitigating and adapting to climate change and sharing sustainability initiatives ranging from water to agriculture.

Financing is another important aspect of international bodies’ roles in addressing climate change and energy needs. Financing from international bodies increases access to climate change solutions for governments that may need it. The World Bank estimates that $93 trillion USD in investments for sustainable infrastructure is needed globally by 2030 with $4.5 trillion USD needed for project planning. Efforts like the Green Climate Fund, the largest climate fund in the world dedicated to providing financing and support to developing nations for implementing their greenhouse gas emissions reduction and improving climate adaptation strategies, help to address this need.

A final aspect of international bodies and their role in climate change is facilitating research agendas. One of the most well-known entities that conduct research related to climate is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). An extension of the United Nations, the IPCC conducts in depth research and assessments on climate change ranging from mitigation to impacts and vulnerability, to be presented to policy makers. The most recent summary and report were completed in March 2023. Research agendas and panels provide consistent methodologies and unbiased results that highlight climate problems and identify an outline and actions in mitigating and adapting to climate impacts.

National Governments

National governments play similar roles to international bodies by setting the agenda and priorities within their own borders and influencing the direction of international dialogue. National governments’ involvement in international assemblies and meetings imbues these multistakeholder discussions with their authority and direction, and can determine climate priorities that include food production, freshwater access, energy production, and public health. It is critical that every level of a national government is included in dialogue around mitigating and adapting to the impacts of climate change.

For example, the United States has frequently played a leadership role in international conversations around climate change and the environment and its representatives to international bodies have signed many agreements. However, the actions and strategies identified by these agreements have not always been fully implemented in the United States due to a variety of factors. One is the difference between the branches of government that negotiate and enact agreements. Climate and energy strategies require financing and funding to be effectively implemented, and the United States Congress, the legislative body, oversees the federal budget and spending. If the President of the United States or representatives plan to agree to a climate accord, it is crucial to include participation from leadership and members of the United States Congress to chart a successful path toward enacting any actions they agree to. When the Trump administration came into office in 2017, the United States withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement until the Biden administration recommitted the United States in 2021. Stronger participation from the United States Congress could have seen committed funding and policies towards priorities related to the Paris Climate Agreement whether the United States withdrew from the agreement or not.

Additionally, national governments act independently, with or without international funding, to address their own countries’ specific climate change impacts by funding climate initiatives and developing strategic plans guiding their citizens and industries in reducing global emissions. In 2019, Costa Rica developed its National Decarbonization Plan summarizing actions in transportation, energy generation, and energy use in buildings across multiple sectors to be taken by Costa Rica for net-zero emissions by 2050 with engagement from federal agencies, private companies, and cities. In 2021, Nigeria developed the 2050 Long Term Vision for Nigeria (LTV 2050) which recognizes the influence of oil production on the country’s economy and environment and outlines their vision by sector in achieving a fifty percent reduction from its current level of emissions by 2050. Of the top ten emissions producing governments, seven – China, the United States, India, Russia, Japan, Indonesia, and Canada – have created long term plans to meet the goals agreed upon in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. The twenty-seven countries that make up the European Union are grouped together and are considered one of the top ten emission producing governments, although several members of the European Union have created individual long-term plans.

International Success

Despite impediments to progress, nations and international bodies have achieved successes cooperating and collaborating on energy production and protecting the natural environment and impacted communities. Given the difficulty involved in achieving them, it is important to note our successes in combatting climate change and improving the natural environment. At the international level, the Montreal Protocol is one of the most notable of these successes.

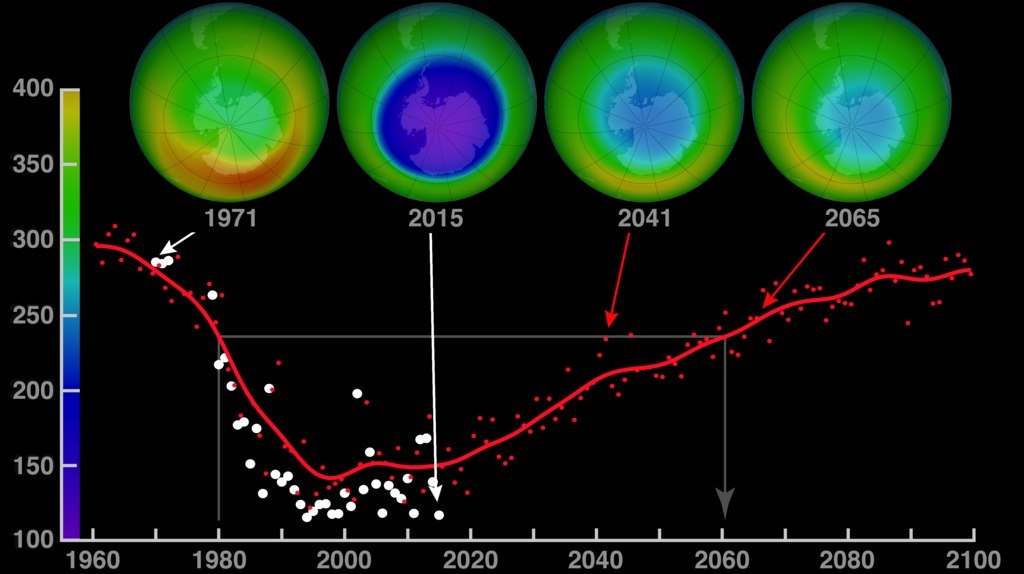

In 1974, two chemists, Sherwood Roland and Mario Molina, determined that almost one hundred man-made chemical substances found in refrigeration and air conditioning, among other every day products, were depleting the ozone layer. Comprised of oxygen molecules (O3) in the atmosphere, the ozone layer serves as an essential protective barrier to the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Three scientists from the British Arctic Survey discovered a hole in the ozone layer in 1985. A weakened ozone layer or a hole could increase the chances of skin cancer, cataracts, and impaired immune systems for people around the world.

In 1987, 197 countries signed the Montreal Protocol, the first and only to date United Nations agreement to receive unanimous ratification, detailing steps and actions that signatories could take to phase out man-made chemical substances. Over the past three decades, the UN Scientific Assessment Panel conducted assessments to study the ozone layer and the impact of the treaty, and if signatories stay committed to the policies outlined, the UN Scientific Assessment Panel expects the ozone layer to recover to 1980 levels by 2040. Overall, the Montreal Protocol has helped slow the warming of global temperatures by 0.5⁰C since its implementation began. The hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica has been improving since 2000 with recovery expected by 2066.

As successes like the Montreal Protocol demonstrate, international bodies and national governments both play an important role in facilitation, financing, research, and agenda setting. Every national government and international body must embrace their roles as climate stakeholders, understand the global and local impacts of climate change, and provide consistent direction on effective implementation of strategies. They can ultimately provide frameworks and foundations for smaller stakeholders to implement their own strategies to mitigate and adapt to the numerous climate impacts affecting local communities.

Justin Brightharp is YPFP’s Rising Expert for Energy. He is a Senior Program Manager for the Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance where he serves as subject matter expert on energy-efficient transportation. He develops policy, facilitates stakeholder engagement, conducts research, and manages programs and projects across eleven southeastern states. Justin’s background includes project management and policy at the local level and clean transportation project deployments in the United States. Justin’s thoughts in this article are his own and do not represent the Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance.