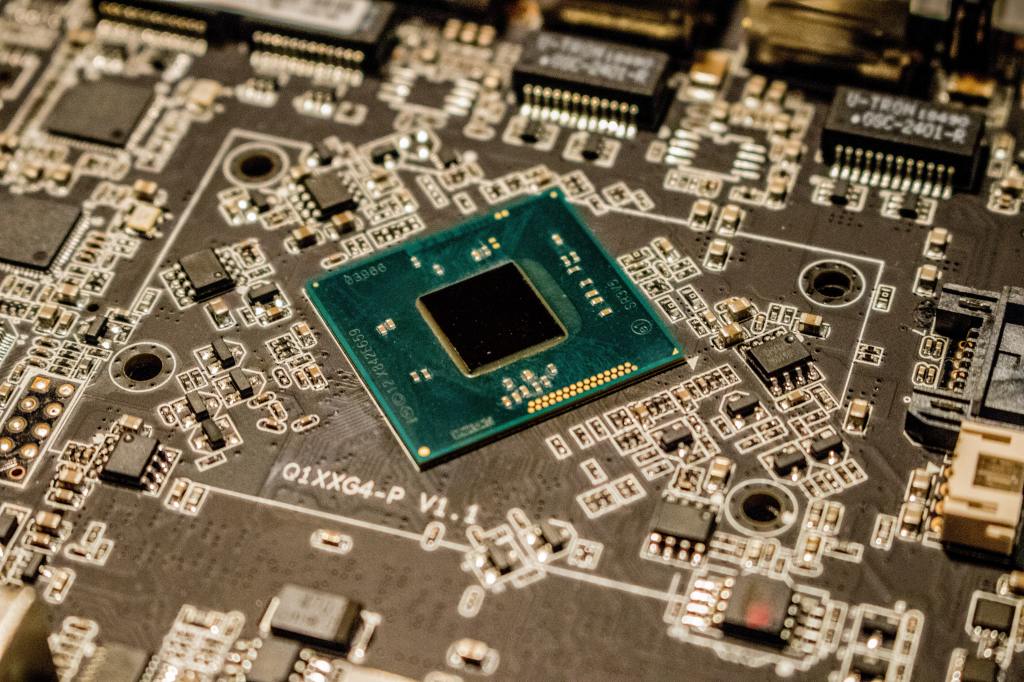

By Jasmin Alsaied | YPFP Rising Expert for National Security | August 20, 2023 | Photo Credit: Pexel

It’s an open question as to whether America’s existing semiconductor infrastructure is poised to manage change. Even with new initiatives, like the monumental CHIPS and Science Act, it’s unclear how much the production process for microchips, microelectronics, and semiconductors, specifically for defense use, will be streamlined. Though the CHIPS Act has the potential to create a robust supply stream of these items for defense use, there’s work to do to identify which companies, which chips, and which security constraints will best advance America’s national security aims. Instead of solely focusing on acquisition and manufacturing efforts, as is done in the CHIPS for America Defense Fund, America’s digital defense architecture must expand and utilize integrated public-private partnerships that leverage the private sector to develop and manufacture semiconductors at scale for immediate use.

Signed into law in 2022, the CHIPS Act allocates nearly $200 billion for the research, development, and commercialization of semiconductor technologies. The bill also earmarks funds for businesses that possess the technology and acumen to develop semiconductors, tax credits for states, businesses, and organizations who can support the CHIPS Act, and further research for more advanced chips. These programs are designed to harness the power of public-private enterprise to ensure that the development digital warfare capabilities is not impeded by chip shortages.

Developing and manufacturing chips isn’t as simple as it sounds. Not all circuits and chips are made equally. Some may require additional configurations after manufacturing. These devices, known as field-programmable gate arrays (FPGA), are important to emerging technology for several reasons. FPGAs allow manufacturers and applications to start system software development by operating with a “programmable” chip – a key to most robust defense applications these days. The technology, high cost of manufacturing, and availability of expertise complicates the production of semiconductors and requires that specific attention be paid to companies and manufacturers that can implement FGPA logic. Any unplanned interruption or halt in the current chip supply chain would render America unable to meet domestic manufacturing demands, let alone those emerging from the military and on the battlefield.

To start, the CHIPS Act must prioritize efforts to ensure that there is a diversity of semiconductor devices that meet emerging demands of the defense industrial base. Today, most defense-grade FPGAs undergo final manufacturing by one subcontractor. This presents significant readiness and resiliency challenges. Introducing new players in the chips community would allow for competitive responses to the Department of Commerce’s current priorities with chips and diversify the stream of companies participating in the chip manufacturing process. This process will alleviate significant supply chain bottlenecks for U.S. semiconductor fabrication facilities producing chips for the defense industrial base. As a result, companies who either possess or intend to invest in semiconductor manufacturing infrastructure will directly support growing defense needs and benefit from the financial incentives laid out in the bill. The Act could then provide more opportunities for a diverse set of private entities to engage in the defense industrial base, which was often unfeasible in the past.

To build the diversity needed to create a robust chips industrial base, the bill must leverage new public-private partnerships to help subsidize overhead costs needed to source and purchase semiconductor materials and manufacturing equipment for companies interested in chip manufacturing. Two organizations from the CHIPS Act – the National Semiconductor Technology Center and the Microelectronics R&D Manufacturing USA Institute – are poised to allocate funds and prioritize supply chain diversification and act as pivotal forces for companies looking to enter the chips industry. This creates fewer barriers to entry for companies willing to research, develop, and manufacture chips at scale for defense needs. Largely, companies, academic institutions, and public-private syndicates who currently hold contracts to support the Department of Defense don’t possess the capabilities to produce or develop their own FPGA chips. The Department of Commerce must continue to establish partnerships with entities through National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to solidify a streamlined manufacturing network that the defense sector urgently needs.

The final challenge for chip manufacturing institutes is ensuring that there are efforts being pursued in the development, manufacturing, and packaging of chips with increased capabilities. Though the Department of Commerce is still working through the details of how manufacturing institutes will play a role in the greater ‘chips ecosystem’, it’s clear that NIST and these institutes will largely shape the direction that is taken to bolster the virtualization and automation of maintenance and the development of advanced test and assembly capabilities. To ensure that a variety of chips are made for multiple uses across sectors, Commerce should focus on enforcing specialties within manufacturing institutes, and streamlining production efforts. This creates greater public-private fusion and alleviates administrative and bureaucratic bottlenecks affecting CHIPS Act implementation.

One focus area that Commerce, NIST, and the manufacturing institutes have yet to prioritize is the fundamental issue of research security and protection. Current security efforts are deficient and lack the detail and rigor needed to be applied across the board to all industry, academic, and government partners. The Chips Program Office, NIST, Commerce, and other partners must also develop guardrails to ensure that monies awarded to companies are not spent on stock buybacks or dividends and that entities do not hold conflicts of interest that work against national security efforts. Until these measures are in place, research security will remain a costly hurdle affecting all organizations in the semiconductor industry. As private companies and government experts begin to source chips to fill critical shortages, security will become the greatest barrier to entry for budding defense entities.

The coming decade will present a technological landscape in which we come together, or fail, as a nation. Semiconductor technologies are critical to that juncture. They will serve as a quantitative measure of success of America’s ability to enact change and develop public-private synergy. A focus on leveraging the public-private nexus remains an efficient way to maximize the CHIPS Act’s ability to support the defense industrial base.

Jasmin Alsaied is YPFP’s 2023 Rising Expert for National Security. She is a United States Navy Surface Warfare officer currently pursuing her master’s in Foreign Service at Georgetown University. Jasmin is also a non-resident fellow at the Middle East Institute.