By Nicholas Barnes | YPFP Member | August 16, 2025 | Photo Credit: Flickr

The United States has spent decades watching competitors use sovereign wealth funds to embed themselves in critical infrastructure around the world, but that era of passive observation may finally be ending. Sovereign wealth funds are state-owned investment vehicles that deploy national capital for strategic objectives. While Norway’s fund focuses on financial returns and Singapore’s balances commercial and strategic goals, China weaponizes its funds to project geopolitical influence. In early 2025, Executive Order 14196 instructed the Departments of Treasury and Commerce to design a national sovereign wealth fund, signaling the United States’ readiness to adopt mechanisms long employed by competitors like China. Public criticism has questioned the wisdom of launching such an initiative amid rising deficits and mounting fiscal pressures. Yet these budgetary concerns, however valid, miss what matters. The fund’s design will determine whether America can finally compete with rivals who have spent decades weaving control into global infrastructure through strategic capital deployment.

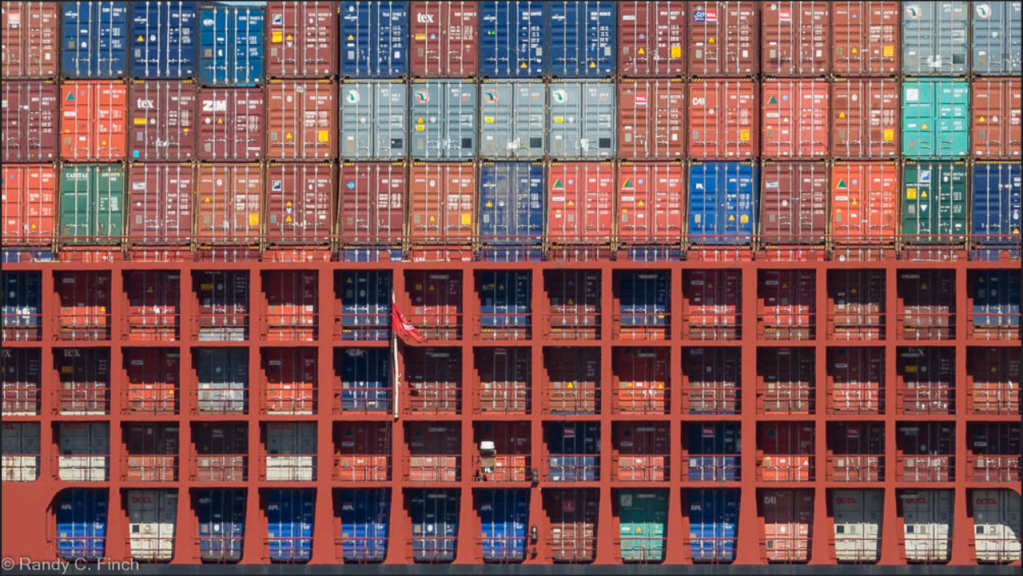

A U.S. sovereign wealth fund serves as a platform for operational engagement. The United States currently lacks a centralized mechanism to allocate capital supporting political objectives across the globe. While competitors routinely use sovereign wealth funds to shape infrastructure, financial ecosystems, and regional control, American efforts remain fragmented across shuttered development agencies and NGOs. The fund’s advantage lies in structuring investment contracts that create operational reliance by requiring specific software, technical services, or management personnel as conditions of investment. These requirements generate infrastructure control that becomes difficult to replace once operational.

The Strait of Malacca offers a clear target for this approach. China imports 85 to 90 percent of its oil through Indonesian waters, creating a critical vulnerability. A U.S. sovereign wealth fund could finance port upgrades in Java and Sumatra, requiring Indonesian ports to use American software for customs processing, cargo tracking, and power infrastructure as a condition of investment. As port operations become reliant on these tools, the U.S. gains quiet leverage over China’s primary oil supply route. If Indonesia later allows Chinese military access or joins restricted Chinese financial networks, the U.S. can simply cut off software support. The ports stop functioning immediately, blocking China’s oil imports without any diplomatic confrontation.

However, such control cannot always be installed remotely, particularly in unstable environments where local capacity is insufficient or infrastructure faces sabotage risks. In these circumstances, a sovereign wealth fund requires direct management through personnel operating under commercial rather than diplomatic cover. When software is first deployed, a critical window exists where local staff require training, infrastructure needs configuration, and control remains fragile. Direct management addresses this vulnerability by placing fund-employed managers in key operational positions during implementation.

This mechanism functions most effectively in weak or failed states where local capacity is genuinely insufficient and foreign management appears necessary. By controlling port authorities, customs administration, and energy distribution during installation phases, direct managers create functional reliance so deeply entrenched that removing it causes collapse. Chinese entities now operate 11 of 46 sub-Saharan African ports through state-owned enterprise concessions. These arrangements involve Chinese personnel managing key infrastructure during development phases that persist after local management assumes operations.

Intelligence collection represents a significant additional benefit of sovereign wealth fund operations. When fund personnel manage critical infrastructure projects, they gain access to data streams that traditional intelligence methods cannot reach. Managing ports exposes regional shipping patterns and supply chain vulnerabilities, while overseeing energy networks reveals industrial capacity and consumption patterns that indicate military capabilities. Telecommunications infrastructure management provides insight into government operations through network traffic and communication patterns. This information gathering occurs under legitimate commercial cover, making it nearly impossible for target countries to restrict access without damaging their own operations.

A potential flaw in this approach is that courts and contracts fail against major powers willing to ignore their decisions. China’s response to the 2016 South China Sea arbitration illustrates this weakness. When the tribunal ruled against China’s territorial claims, Beijing declared the decision “null and void” and ignored it entirely. The Port of Djibouti reinforces this limitation. When London courts upheld DP World’s contract and ordered Djibouti to pay $385 million for violating the agreement, Djibouti simply seized the terminal and expelled foreign employees. This pattern reveals that legal mechanisms work only against countries that prioritize international financial reputation over control. Major powers may conclude that the costs of non-compliance are manageable, making legal frameworks costly exercises with limited effectiveness.

In many scenarios, it becomes advantageous to allow competitors to bear the financial burden of physical infrastructure development while retaining control through operational, legal, or managerial mechanisms. China can fund capital expenditures for ports, railways, and energy infrastructure while the United States retains functional authority through integrated technical platforms, enforceable service contracts, or direct management. This maximizes influence while minimizing financial exposure. Once these controls are institutionalized across multiple targets and mechanisms, the United States gains the capacity to impose consequences through structural terms built into the point of investment. The result is a position of quiet authority that operates through design rather than enforcement, creating sustainable influence without ongoing political capital or diplomatic engagement.

Nicholas Dillon Barnes served as Head of Business Development at SPY Projects Art Gallery in Los Angeles and is a member of the YPFP. He has an interest in intelligence and global markets, and in his free time, he enjoys learning German and Arabic.