By Henry Trop | Rising Expert on Climate Change | December 13, 2025 | Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

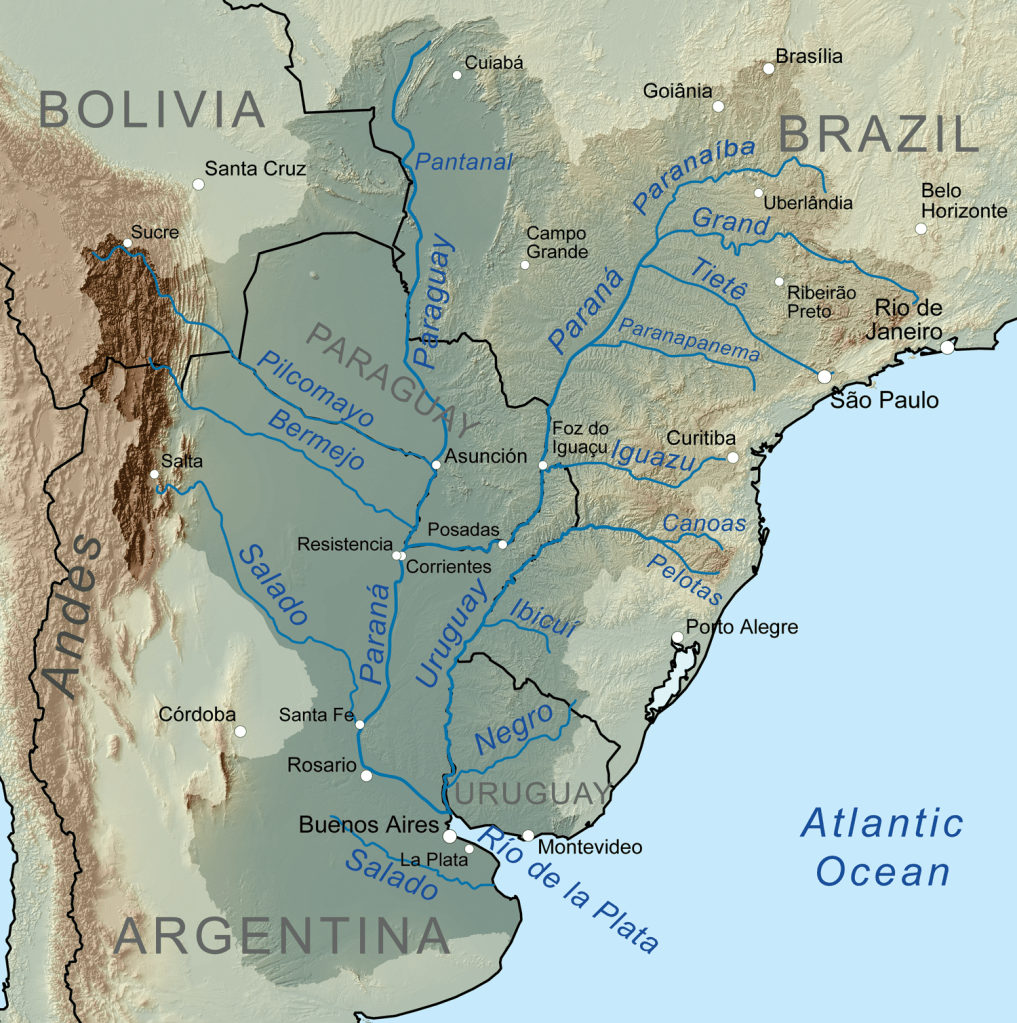

The Rio de la Plata is vast – but not big enough. The political persuasions of the two ruling parties across the water, Argentina’s Buenos Aires and Uruguay’s Montevideo, have incompatible views on how to govern this great body of water: chainsaw neoliberalism and stalwart progressivism. The result will be a real-life political experiment on a grand scale of how two ideologies facing each other across a border impact shared critical resources.

When President Javier Milei swept to power on a ticket of radical privatisation in November 2023, he made no qualms of taking aim at Argentina’s largest state-owned water company (Agua y Saneamientos Argentinos, or AySA). Speaking with TN at the time, the President laid out a central tenet of Milei-nomics: ‘anything that can be managed by the private sector will be…It has been proven that anything the public sector does, it does wrong’.

The chainsaw that everybody saw coming finally arrived in July 2025. The Ministry of Economics announced that 90% of the water company’s share capital would be transferred to the private sector – with 51% sold to a single ‘strategic operator’ – in less than a year.

Former President of AySA in November 2023 – and wife of Milei’s Peronist election competitor – Malena Galmarini stood up to the President-Elect, declaring that ‘our rivers are protected, and water is not negotiable’. By the year’s end she was out of a job.

In the last 12 months, the stage has been set for the sale. The workforce was reduced by over 15%. Tariffs were increased by 209%. Across 2024, AySA achieved its first dollar surplus in its history – and presumably its value at market increased considerably.

The new look AySA claims that, in this time, pollution across Buenos Aires waterways has not increased; it remains to be seen whether this will continue to be the case.

Either way, President Milei is unlikely to care. In September 2023, on the election trail, he asserted that ‘a company can pollute a river as much as it wants’ because ‘no one can claim ownership of rivers’. Hundreds of environmental campaigners gathered in front of the stone Palace of the National Congress in March to protest under the banner that ‘water should not be a privilege’ – but wider protests have yet to take off.

Meanwhile, in February 2025, Buenos Aires’ Sarandi River ran red with the effluent of a leaking dye factory.

Across the bay in Uruguay, the waters are not wave free. In 2023, a regional megadrought across the two countries left Montevideo’s main reservoir with only 10 days left of water. The government was forced to mix stored water with the brackish and contaminated water of La Plata.

Since 2004, access to clean water has been defined as a fundamental human right in Uruguay. The amendment to the constitution that ratified this was overwhelmingly supported in a public vote by almost 65% of the electorate. The country is unique in South America for effectively banning the privatisation of water resources.

In March this year, Yamandu Orsi – a smooth progressive left politician – was cautiously voted in as President of Uruguay after a narrow victory in a run-off against a centre-right coalition. One inherited challenge for the government to navigate was the Neptuno Project – a water intake and treatment plan on a grand-scale. Motivated by the near-catastrophe of drought, Neptuno was designed to produce 150 million litres of drinkable water per day.

There was one problem: the construction and operation of the factory would be funded in part by private investors. Civic uproar followed. The Federación de Funcionarios de OSE – the union of the state water company – declared the project unconstitutional and threatened to strike.10,000 signatures were gathered in March to stop the construction.

Faced with the blowback, a court suspended the project license, and the Orsi Government pulled the plug. On the same month as Milei announced the privatisation of Argentina’s largest state-owned water companies, Uruguay’s brief flirtation with privatisation lies dead in the water.

Presidents Milei and Orsi have kept their relationship to polite platitudes. Milei chose not to attend Orsi’s inauguration but did retweet the Foreign Ministry’s commendation on his election: ‘“The Argentine Republic congratulates the Uruguayan people for their exemplary civic day and salutes President-elect Yamandú Orsi on his victory. Meanwhile, Orsi has appealed to reason. For him, their relationship ‘has to be good’ despite ‘difference perspectives’ on matters of ‘philosophy [and] ideology’.

But what plays out on banks of the Rio de la Plata will be a grand experiment of politics: to privatise or not to privatise?

Argentina has been crippled by runaway inflation, which topped 25.5% in the month of December 2023. But supporters of Milei’s ‘economic miracle’ characterised by a wave of deregulation and privatisation has seen monthly inflation reduce to less than 2% in June 2025. In turn, a wave of unemployment – rising by nearly 8% in the first quarter of 2025 – has inundated the country. In any case, in Milei-nomics, there is no fiscal room for AySA’s expenditures of over USD 600 billion – and so it had to go.

Those suspicious of privatisation may point to the troubled history of privatisation of water companies in Argentina. In 1993, a concession was granted to Aguas Argentinas, an investment consortium led by international backers including the French Suez Company and the British Anglian Water, to manage Buenos Aries’ supply. In that time, tariffs were significantly hiked and the water infrastructure in poorer areas of the city was underinvested in.

The political experiment being conducted on the Rio de la Plata represents a broader game being played on the borderlands between countries – that is the entrenchment of differing political ideologies across shared geographies. It arises when hardline politicians are confronted with degraded shared resource pools – and decisions around adaptation are hamstrung by political intransigence.

It’s a game rippling out across the world this year. Between Canada and the United States to India and Pakistan. On the border it can be hard to find a middle ground.

Henry Throp is a doctoral researcher at the University of Oxford working on using deep learning to investigate environmental resilience. He also works as a researcher on water insecurity at FAIRR Initiative and as the Rising Expert for Climate, Energy, and Environment at Young Professionals in Foreign Policy.